While studying Digital Anthropology, digital divide was a topic which often came up for discussion in the classes. Digital divide which clearly demarcates those with access to technology from those with limited, borrowed or no access to technology. In this context, the stories of Yahoo-Yahoo Boys of Nigeria and the cyber-cafes in Ghana make very interesting reading. In my own country, digital divide has spawned into new forms of social and cultural equities.

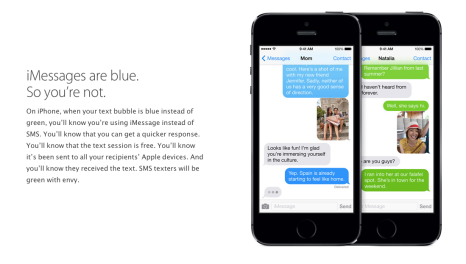

So, I was so amused when I read Paul Ford’s ‘It’s kind of cheesy – being green.’ There’s a point in his post where he highlights Tim Cook’s quote from a WWDC event in which he had mocked upon the green bubbles. But are the green bubbles really ugly? Ford highlights how these are purely product decisions clearly in this case, to make the ‘iDevice’ user stand out from the rest. It’s now even a selling point! However, what appears stranger to me is the fact that the icon for Messages in the iOS universe is green and not blue.

It’s a little thing, so very little, but it matters. Perhaps, one small factor among many that allow the iPhone to sustain higher prices and margins and for people and societies to form opinions. There are many studies which show consumer decision making gets strongly anchored to a product or an association as an effect of colours. The whole business around cherry-picking colours for different product attributes is now so well-entrenched industry trend, that Pantone, the proprietary colour-standardization company, has been for a couple of years has been selecting ‘colour of the year’ to influence design and product decisions from fashion to home, and packaging to interactive design. How they pick the colour of the year makes another very interesting story.

As a final word, I don’t think Apple did the iMessage colour coding on purpose but the decision around selecting blue over green has led to multiple ramifications impacting societal and cultural norms.